Today my Facebook feed had several people sharing an OnstageBlog.com article from December 2017 titled “Keep Calm and Manage On : The Importance of Being an Even Tempered Stage Manager.” I admit, I clicked on the link with a bit of trepidation, wondering how I would feel about it.

I know that “calm” is a word a lot of people use to describe “perfect” stage managers. Inside, I often do not feel calm as a stage manager. I am frequently multitasking like a fiend during rehearsals, especially if there is a limited amount of staff and it’s a big project. I may be timing entrances, on book/script for an actor who calls “line,” tracking blocking of both people and props, noticing that an actor is looking a little pekid, trying to decide how many texts or emails are really important to look at (for those people who expect me to be always available as a stage manager, which isn’t really feasible), and also keeping an eye on the clock for breaks. Is that calm?

As I read the article, however, I found myself nodding in agreement. The first thing it addresses is the idea some young stage managers have that they have a “stage manager personality” separate from their real personality. I like the way the article explains that being mean is not a great way to lead, and you should be authentic at the same time. I hate when I hear someone say that stage managers “like to boss people around.” That is not a reason to get into stage management, nor an appropriate subject for stage management memes, in my opinion.

After this, Claudia Toth’s article gets into being calm in an emergency. I think there is an appearance of calm and collected (and much of it is real) that is exactly the right thing. As Toth stated, “Urgency is good, action is good, and panic is bad.” That doesn’t mean I’m laid-back and blasé about issues that arise, but that it’s not the end of the world. Shows can (and do) stop. Emergencies happen. Change happens. The more prepared you are and know the factors involved in your show, the better you can expect the unexpected and adapt. Bring your team together to help sort out the situation, too. A stage manager doesn’t have to know every answer, it’s how to use your resources wisely. I’ll give an example.

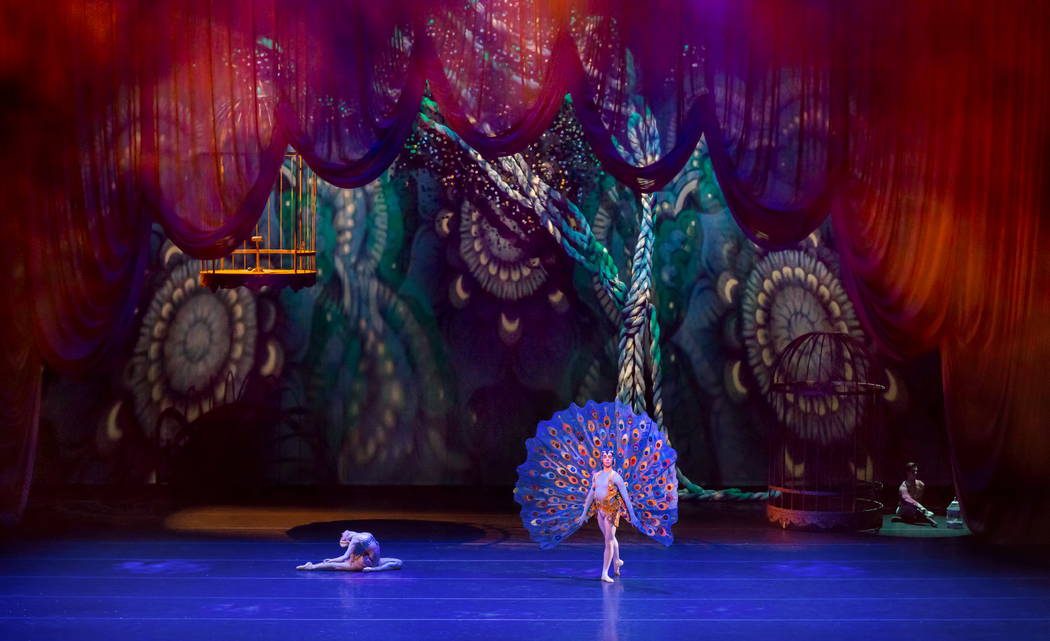

During a performance of The Nutcracker, I called the Show Scrim and Blackout in for a shift that was covered by a 24-second video projection. Over headset soon after, I heard, “The Austrian’s caught and we’re going to have to stop the show.” I quickly asked if the blackout right behind it was free and working, and if it was safe to leave the Austrian all the way out. (Yes, it could be taken out higher than the lights it was hanging up on, and out of the way, but not brought in without getting caught. We could use the US Blackout for the next scene shift a little later in the act.) Next question, was our performer who was already preset in the grid safe to come in on cue? Affirmative on both counts. Great, that could get us through at least the next series of shifts – certainly the rest of the video remaining and time to reassess. “So we’re continuing on?” “Yes, without the Austrian, unless you can see another reason to stop.” He agreed with the call, performers were notified, the video ended, and I called two-thirds of the next shift to get us into the next scene; no need to call the Austrian – which I announced as such in the standby – but we were still able to do a bleed through with the front Show Scrim and DS Blackout on their usual cues. We all knew that the set wasn’t quite as pretty as designed, with some things on stage looking a tad scrunched towards center (without a picture frame surrounding it – see image below). However, the show didn’t have to stop. Once that scene was in full swing, we continued talking through our options and decided we were good to go. I adjusted a couple cues a few scenes later where normally I would have called first the Austrian back in, and then its US Blackout (followed by the reverse to get out of that shift), but most of the show we were able to continue normally. There was actually a famous choregrapher duo in the audience that night who came backstage after the show. They were introduced to the assistant stage manager and I, explaining what our roles were, and the word “Flawless!” came out of the woman’s mouth. She then went on to explain how smoothly all of our scenery moved on and off, etc. “Thank you,” I said with a big smile. See? Even people who know what stage managers do don’t know what we do behind the scenes, yet we are appreciated. Especially if we remain calm and collected. Did I then go home and message and/or call other stage managers to say, “Guess what happened?” Yes! Were my words calm then? Probably not!

Meanwhile, on a completely different note, another article that came across my feed today was about how some operas have a very different sense of timing for scene shifts, particularly older ones. That certainly took me a lot to get used to when I started stage managing opera. Check out “A Funny Thing Happened at the Opera” by Christopher Frizzelle on TheStranger.com for a recent anecdote from Seattle Opera.